AMD inside

AMD INSIDE – An unholy alliance or the inevitable next step?

Jeremy Laird investigates Intel’s new processor that includes a high- performance AMD GPU

AN AMD GRAPHICS CHIP inside an Intel processor? Not in a million years. But that is precisely what Intel recently announced: a whole new product line that combines an Intel CPU with an AMD GPU in a single processor package.

More specifically, it contains a quad-core CPU and a high-performance AMD GPU. The new chip is intended to enable the creation of a new generation of thin and light laptops with serious performance. Enough performance to play AAA games, deliver a quality VR performance, and support pro-level content creation.

If it seems like an unholy alliance between confirmed enemies, there are not only major upsides for both Intel and AMD—the new chip also represents the logical next step for the PC as a platform in both mobile and desktop forms. However, it being a logical next step does not necessarily mean the eventual outcome will be predictable. Intel and AMD’s alliance will almost certainly revolutionize both the physical architecture of the PC and the key relationships that have defined the industry for a generation. If the impact the new technology will have on the PC as a device is straightforward to grasp, it’s far from clear how the balance of power between the major players will shake out.

For starters, if the fusing of CPU and GPU functions into a single package is the future of not just entry level systems but high-performance content-creation and gaming PCs, does this mean Intel will be reliant on AMD’s help going forward? Likewise, missing so far from this picture is the final member of the uneasy triumvirate that rules the PC: Nvidia.

At first glance, this development doesn’t look good for Team Green. Nvidia currently lacks an obvious route to do something similar, and insert its graphics technology on to a CPU package. In the long run, if this new CPU-GPU approach ends up being the default configuration for performance PCs, it certainly seems like Nvidia won’t have a place at the table. But, as we’ll see, there’s much to play for. This is just the first move.

Are the political machinations that have enabled this new Intel-AMD mega chip to exist more interesting than the technical details? That might just be true, but let’s start by squaring away the details of what Intel announced, and also consider some of the secrets regarding its specifications that have since emerged.

THE POWER WITHIN

The basics involve a single processor package that combines four major elements. The first two are the previously mentioned Intel CPU and AMD GPU. Intel says that the CPU is one of its Kaby Lake generation Core H series mobile chips. That indicates a quad-core processor somewhat incongruously equipped with its own integrated graphics functionality.

It’s possible Intel has created a new spin on the Kaby Lake Core H, with the integrated graphics stripped out. However, given this is initially aimed at creating thin and light laptops, there are clear benefits to keeping the Intel integrated graphics. It allows for low-power operating modes and extended battery life when full graphics performance from the AMD GPU isn’t required. The probability, then, is that the CPU part of the package is more or less straight off Intel’s shelf. Hold that thought.

Part two is the AMD Radeon graphics. This is where the bespoke engineering begins. Our understanding is that the AMD GPU is a custom chip created expressly for Intel. In fact, it has to be precisely that, based on further elements we’ll come to shortly. What it isn’t, however, is a radically advanced chip from a 3D rendering perspective. It’s listed in leaked specification sheets as an AMD Vega M GH Graphics GPU, although what that actually means isn’t totally clear at this point.

Specification and benchmark leaks involving some early development systems based on the new CPU-GPU package suggest some further details for the specs of the graphics part of the package. Two iterations of the product have been seen, known as the Core i7-8705G and the higher performing Core i7-8809G. In top spec, the AMD GPU looks to be a 24 compute unit item. Two variants have been seen in the wild: one with a GPU clock speed of 1GHz, the other 1.2GHz. Do the math on the compute units, based on existing AMD GPUs, and you have 1,536 unified shaders.

For context, AMD’s Radeon RX 480 has 2,304 shaders, and the most powerful RX 470 cards have 1,792 shaders. Of course, neither of those are close to being AMD’s top-performing GPUs, which are based on the newer Vega architecture. Another interesting reference point involves games consoles. Both the Sony PlayStation and Microsoft Xbox now use AMD graphics technology, albeit from a slightly earlier generation of AMD graphics than Polaris. The original Xbox One boasted 768 unified

Is this unholy alliance between Intel and AMD the beginning of the end for Nvidia? At first glance, it looks as though Nvidia simply cannot respond. It doesn’t make x86-compatible PC processors, and it lacks the required license to do so, even if it wanted to. It seems very unlikely that Intel would pair with Nvidia on a CPU-GPU product. Likewise, why would AMD put Nvidia graphics into a package when it has its own high-performance GPU architectures?

When you think about it, Nvidia can only sell graphics to consumers because Intel and AMD allow it. It’s Intel and AMD that control the platforms and the interfaces that allow GPUs to communicate with CPUs. Eventually, these new CPU-GPU packages may come to dominate the market, with both Intel and AMD doing their own versions based on 100 percent in-house processor and graphics technology. In this scenario, Nvidia is a goner. It has no relevant x86-compatible PC processor technology to call upon.

But hang on: Nvidia is hardly dumb to this possible end game.

That’s no doubt why it has pushed hard in recent years to broaden its horizons.

ARM chips, chips for conventional cars today and autonomous cars tomorrow, industrial parallel compute through general-purpose GPU products—Nvidia has been working hard on all of this, and more.

On the one hand, it could all come down to how hard Intel will push this new high- performance CPU- GPU paradigm, and how quickly the rest of Nvidia’s business can grow to replace dwindling consumer graphics sales. In that case, it’s all rather ironic, given the current strength of Nvidia’s consumer GPU business, and the rosy outlook for PC gaming in general.

But here’s the catch:

If Intel can go to AMD for graphics, could Nvidia hit up AMD for CPUs, and create a CPU-GPU package to take on Intel? In the short to medium term, a multi-chip package like the new Intel product looks plausible. Further out, high- performance CPU and GPU tech seems likely to fuse into a single chip, and that may raise licensing problems. Would Nvidia need an x86 license to sell such a chip, even if the CPU part of the design was supplied by AMD?

The fastest graphics cards, such as the Nvidia GeForce GTX 1080 Ti, probably have nothing to fear. For now.

Could a laptop as thin as the Apple 12-inch MacBook soon offer gaming- capable graphics?

makes for a thicker overall package, and it also has power management implications.

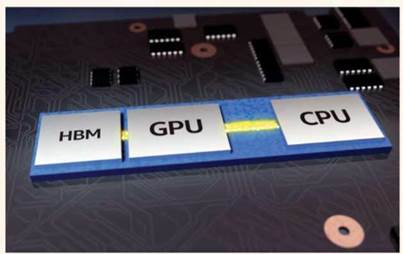

The full specifications of Intel’s HBM2 and EMIB solution haven’t yet been revealed, beyond the use of a single 4GB chip of stacked HBM2 memory, although it is the first time HBM memory has been used in a mobile platform. What’s more, it’s this use of the EMIB that dictates a bespoke GPU. Support for the EMIB has to be built into the GPU itself, a feature that thus far only exists in a handful of high-end AMD GPUs. Whatever, the overall solution is clearly designed to deliver memory bandwidth that’s of the order of discrete desktop graphics boards, and deliver that groundbreaking performance for what could be described as an integrated graphics solution.

All told, and even without considering the politics of the Intel-AMD relationship, it’s fascinating from a technical perspective. The big question is whether it represents a glimpse of the future. Is this what not only laptops but also desktop PCs will look like in the future? That’s been the assumption almost certainly be unprecedented for a GPU highly integrated into a thin and light laptop PC. That’s arguably only possible thanks to the last two major elements of the processor package, which involve dedicated memory for the GPU, and an exotic new interface to connect the two.

MAKING CONNECTIONS

It’s memory bandwidth, of course, that has thus far prevented so-called CPU-GPU fusion chips from serving up serious gaming performance. Previously, all such chips have shared the CPU’s external memory controller with the GPU, and that has meant frankly pitiful memory bandwidth by GPU standards. But Intel’s new beast has a full 4GB of stacked High Bandwidth 2, or HBM2, memory hooked up to the GPU via its own proprietary interconnect, known as the Embedded Multi-Die Interconnect Bridge, or EMIB for short, and the fourth and final major element of the new product.

The advantage of EMIB is that it integrates the interconnect into the package substrate, but does so while offering far higher connectivity density and therefore bandwidth than ever before. Previously, achieving high bandwidth through the package substrate hasn’t been possible. So, a silicon interposer sitting atop the substrate and underneath the chips has been used. That’s more expensive, it shaders, while the much-improved Xbox One X packs 2,560 shaders. The new Sony PlayStation 4 Pro, meanwhile, rocks 2,304 shaders.

Anyway, factor in the clock speeds of the higher performing Core i7-8809G (which may be far from final), and the resulting performance of the CPU-GPU package from a gaming perspective likely falls somewhere between the Nvidia GeForce GTX 1050 Ti and 1060 desktop graphics chipsets. A solid gaming proposition to be sure, especially for a mobile platform, if somewhat marginal, given that Intel has specifically called out VR gaming as a core competence for the new product. That’s either a stretch by existing metrics of what constitutes VR-capable games performance (the GTX 1060 is pretty much a bare minimum), or Intel may have more powerful versions of the new product that have yet to be spotted in the wild.

Of course, however the precise performance eventually turns out, it will

The performance likely falls between the Nvidia GeForce GTX 1050 Ti and 1060. What would motivate AMD and Intel to get into bed like this?

The AMD graphics part of the new chip has been specifically designed for the task.

ever since Intel first integrated graphics into its CPU packages, but thus far, such fusion processors or APUs have been a low-cost solution. This is the first time that anyone has taken a genuine tilt at creating a single-package product with bona fide gaming and content creation capabilities.

While we wait to discover just how fast it will be, and just how thin and light the laptops are that it enables, the question of what it all means for the industry is plenty to keep us going. What would motivate AMD and Intel to get into bed like this? The answer to that is different for each company.

For Intel, using an AMD GPU is part of a two-stage plan, and a shortcut on its journey toward an in-house integrated solution. While the news did come as a shock, in hindsight, Intel’s integrated strategy has hinted at a move like this for a while. When Intel originally put graphics cores into its CPUs, bold claims were made for progressing 3D rendering performance with each successive iteration. For a while, Intel more or less delivered on that promise. More recently, progress has slowed, and it became clear that Intel’s in-house graphics architecture had lost momentum. What’s more, while Intel’s integrated graphics performance improved, so did the performance of discrete 3D cards. Likewise, PC games only become more graphically demanding over time. The upshot is that Intel’s integrated graphics are no closer today to being truly gaming capable than they ever were. Something had to change.

RIVAL REVELS

In the long run, the plan for Intel is to totally reboot its own graphics tech by creating its own competitive high-performance 3D architecture (see boxout, left). In theory, having its own competitive in-house graphics means Intel will eventually be able to create single-package solutions based exclusively on its own technology. In the meantime, however, Intel simply didn’t have suitable graphics technology to make a high-performance product possible. That Intel nevertheless felt compelled to press on and was willing to use technology supplied by its arch rival AMD very likely points to the other major factor providing motivation: Intel wants to hurt and just maybe kill Nvidia.

Currently, Nvidia absolutely dominates the market for consumer discrete graphics chips. It sells around three quarters of such products bought by consumers, with AMD picking up the rest. That’s a high value market in its own right. It’s also a market that’s growing while the rest of the PC continues its gentle decline. Jon Peddie Research reckons the market for gaming PCs hit billion for the first time in 2016, well up on the estimated billion the market accounted for in 2015.

As Jon Peddie Research says, “The average PC sale is increasingly motivated by the video game use model, which is important to understand in a stagnant

Forget Larrabee, this time Intel is serious.

Remember Larrabee, Intel’s last grand plan for graphics domination? That was based on a radical new approach to graphics processing. In simple terms, Intel planned to use its chip-production technology advantage to cram scores of small x86 CPU cores into a single chip, and use brute force to render fast 3D graphics. The idea was to launch consumer graphics cards using Larrabee chips in 2010.

That never happened. Turns out, even with the might of Intel’s chip fabs behind the idea, Larrabee was simply going to be too slow. Indeed, it’s an indication of just how hard it is to break into the high-performance 3D rendering market that even Intel majorly misjudged its entry. So, once bitten, twice shy?

Not for Intel. Getting into graphics is simply too important, what with the money in the consumer PC market increasingly moving into relatively high-

end performance and gaming rigs, while basic all-purpose PCs continue to be replaced by other general-purpose computing devices, such as tablets and phones.

So, it arguably shouldn’t be a surprise that Intel has announced plans to have another crack at discrete PC graphics. This time,

Intel is serious. It says it intends to create a full top-to-bottom GPU family, including genuine high- performance graphics for gaming PCs. To do that, it has pulled off something of a corporate coup.

Intel has lured AMD’s chief graphics guru, Raja Koduri, who joins Intel and goes straight in as senior vice president of the Core and Visual Computing

Group, and chief architect of its graphics products.

Currently, the time frames and basic nature of Intel’s plans for in-house graphics are unclear.

The new AMD Inside processor indicates that Intel knows it will be some time before it can insert its own graphics tech into such a chip, however. That leaves the big question of whether Intel will be using Koduri’s brains to come up with something new, or take its existing Gen 9 integrated graphics and scale it into something that can compete with the big boys. It will probably be getting on for five years before we know if Intel’s latest play for graphics domination is a goer.

or declining overall PC market. As basic computing functions become more entrenched with mobile devices, the PC ultimately becomes a power user’s tool.”

The problem for Intel in that context is that it currently doesn’t have a dog in the fight for one of the two key high- performance components in a PC: the graphics. With high-performance PCs increasingly becoming the industry’s cash cows, at least in terms of consumer boxes, that isn’t something Intel can tolerate. And given it’s Nvidia that dominates the graphics half of the market, it’s Nvidia that Intel has inevitably set its sights upon. Eventually, Intel will have its own graphics, but for now, the AMD GPU allows it to begin to squeeze Nvidia out of the high-performance consumer graphics market.

If the motivation for Intel is obvious, what about AMD? Surely the last thing AMD wants to do is aid and abet Intel as it plots to assimilate the PC graphics market? Up to a point, that’s true. Another competitor to AMD’s graphics competence is hardly desirable, but the harsh truth is that AMD needs whatever money it can get. History shows that even when AMD has fairly unambiguously superior graphics products, it struggles to gain market share over Nvidia. AMD has never had the marketing clout or wits to compete with the slick self promotional machine that is Nvidia.

HOBSON’S CHOICE?

So, what seems like an unholy alliance with its arch enemy in the CPU market is actually one of the few realistic options AMD has of increasing its market share in consumer graphics. Intel will no doubt drop AMD like a stone the moment it has developed competitive graphics of its own, but in the meantime, the deal brings real money to AMD at the direct expense of its only current rival in graphics, Nvidia.

Further out, a stronger, better financed AMD may well be able to compete with Intel with its own high-performance CPU- GPU package. In Ryzen, AMD finally has a competitive CPU product, and while its Vega graphics architecture has been something

Intel’s tiny NUC system will benefit from the new CPU-GPU technology.

Putting a CPU and GPU into the same processor package is not a new idea. Intel and AMD have been doing it for years. In fact, they’ve fused the two into the same slice of silicon, not just put them into a shared package, but as yet, neither has created a CPU-GPU product with genuine high- performance credentials, not from a 3D rendering and gaming perspective at least.

Part of the reason for that comes down to power consumption and thermals. Combining two high-performance components concentrates power consumption and heat dissipation into a very small space.

It also makes for very large chips that can be expensive to produce.

But all of that is more a problem that prevents competing at the very highest level. As the latest Xbox One X and Sony PlayStation 4 Pro consoles prove, it is possible to create a single-chip solution capable of high- performance gaming. Instead, as far as the PC is concerned, the problem is memory bandwidth. Thus far, the CPU-GPU fusion chips, or APUs as they are also known, have used a shared memory controller for both parts of the chip. Worse, they’ve used a standard CPU spec controller with much less raw throughput than the superwide controllers that are used by discrete graphics chips.

That kind of graphics controller, paired with multiple graphics memory chips, isn’t viable for a single-package product that also houses the CPU. The solution is High Bandwidth Memory, and, more specifically, the second generation version of the technology, known as HBM2. For starters, HBM2 uses layers of memory stacked on a single chip. That means all 4GB of graphics memory in the new Intel- AMD package is housed within a single HBM2 chip. That happens to be good for overall package size.

HBM2 also has a superwide memory interface at a full 1,024 bits for each memory die. That compares with the dual 64-bit controllers of mainstream CPUs.

That superwide interface allows HBM2 memory systems to offer big bandwidth at relatively low frequencies—perfect for keeping a cap on power consumption and heat dissipation. Just one HBM2 memory stack can achieve 256GB/s of raw throughput for the GPU alone. Existing APUs are limited to around 50GB/s, shared with both the CPU and GPU elements.

of a disappointment, as part of a CPU-GPU package, it will still be a tough combo for Intel to beat on its own. That AMD has gained experience with the GPU half of creating a high-performance unified package with HBM2 memory, courtesy of the Intel deal, will hardly hurt. In short, AMD is the great survivor, and the deal is expedient. It allows AMD to fight on another day.

For us PC buyers, the impact of this new approach definitely has several upsides. Squeezing true high-performance CPU- GPU tech into smaller, slimmer packages than ever before will allow whole new classes of performance PCs to be created. Thin and light laptops are part of the early sales pitch from Intel, and very welcome they will be, too. We also expect to see the new package pop up in Apple’s MacBook products sooner rather than later. Indeed, it’s exactly the kind of technology that may enable Apple to apply an extreme makeover to its iMac range, too, and create an all-in- one rig unlike anything we’ve seen before.

Leaked Intel road maps also reveal a new high-performance Intel NUC system, codenamed Hades Canyon. Due to go on sale at the start of the year, the Hades Canyon NUCs use the new Intel-AMD package, and the high-end SKU is being pitched as VR-capable to boot. Suddenly, Intel has a tiny, living-room-friendly box with genuine gaming capability. It’s probably a stretch to say Intel can take on the big beasts of console gaming, but a product like Hades Canyon is a decisive step in that direction.

As for when this technology will roll out on a broader scale, Intel is being fairly cagey, but you can expect to see the first laptops appearing in early 2018. Much will depend on how Intel prices the new package, and how aggressively it incentivizes laptop OEMs, but we reckon Intel wants to do serious damage to Nvidia, so numerous design wins seem likely. If anyone has the clout to supercharge adoption of a new class of processor, it’s surely Intel.

Will Intel deliver on its claims of VR-capable performance?

Intel isn’t just sticking an AMD graphics chip into the same package as its CPUs. Intel also now plans to compete directly in the high-performance GPU market with its own in-house designs. The endgame seems pretty clear—namely a unified high-performance solution that combines full CPU and graphics capabilities, and pushes all of Intel’s major competitors in the performance PC market to the sidelines.

But hang on: There’s another company that has both high-performance x86 CPU and graphics technology. That’s AMD, and in fact, it’s the only company that currently has both in-house. For Intel, high-performance in-house graphics is merely an aspiration at the moment. If Intel’s big new idea with its CPU- GPU package is so clever, surely AMD can simply do its own version long

before Intel can catch up on the graphics side?

On paper, that’s true. In practice, AMD struggles to sell its products at the high end, even when competitive. AMD could very well produce an outstanding CPU-GPU package and struggle to get OEM PC builders to adopt it. It just doesn’t have the marketing clout to fight off Intel’s aggressive tactics.

Oh, and if you are wondering, AMD’s new CPU-GPU chips, or APUs, codenamed Raven Ridge, are not competitors for the Intel package, with performance AMD graphics and HBM2 memory inside. Currently, Raven Ridge is available in two Ryzen APU models: the Ryzen 7 2700U and Ryzen 5 2500U, both aimed at laptop PCs. Yes, Raven Ridge does combine AMD’s fantastic new Ryzen CPU with its latest Vega graphics. In fact, it does so on the same slice

of silicon, not just in the same package. But it’s that tight integration that reveals the real target for Raven Ridge: Intel’s existing laptop processors with integrated graphics. The top Ryzen 7 2700U version of Raven Ridge offers 10 AMD graphics compute units, which works out at 640 unified shaders. That compares with 1,536 shaders in the Intel-AMD product, albeit of a slightly different spec.

Raven Ridge is also a conventional APU in that the GPU part of the chip must share access to memory with the CPU via a standard memory controller. With current PC system memory performance, that pretty much makes it impossible to support high-resolution 3D graphics. CPU memory controllers and DDR4 RAM don’t offer nearly enough bandwidth for the GPU alone, let alone when sharing resources with the CPU.

Intel doesn’t have a dog in the fight for one of the key high- performance PC components.