Evolution of computer

In a world of competing processors and operating systems, John Knight explores how the PC began. Read our Evolution of computer.

THE PC. The personal computer. The IBM-compatible. Whatever you want to call it, somehow this machine has maintained a dominant presence for nearly four decades.

If you try to launch a program from the ’80s to the 2000s, you have a good chance of getting it to launch—your PC has backward compatibility going right back to the ’70s, enabling you to run pieces of history as though they were from yesterday. In fact, your computer is brimming with heritage, from the

way your motherboard is Laid out to the size of your drive bays to the Layout of your keyboard.

Table of Contents

- THE LEAD UP TO THE PC

- Who made the first computer

- ASSEMBLING THE CREW

- Desktop Predecessors – first ever computer

- When was the first computer made ?

- DEVELOPING THE PC – development of computer

- THE IBM-COMPATIBLES

- ENTER THE 386

- The OS Wars Begin

- THE 32-BIT ’90s

- THE MULTIMEDIA AGE

- The 386 and the 32-Bit Era

- THE PERFORMANCE AGE

- BeOS – The sleek alternative

- THE NEW CENTURY

- PLATFORM SHAKE-UPS

- The Raspberry Pi Revolution

- THE VISTA HITS THE FAN

- WHERE ARE WE NOW?

- What About SteamOS?

Despite the weight of all of this Lineage, we have an extraordinary range of devices that somehow get Lumped under the category “PC.” Go back to the early ’80s, and “PC” would evoke a desktop box from the business colossus IBM, but now the name doesn’t belong to anyone, it still survives as “the PC.”

Flip through any PC magazine and you’LL see everything from bulky desktop computers to sleek business Laptops; from expensive file servers to single-board devices only a few inches big. Somehow, all these machines are part of the same PC family, and somehow they can all talk to each other.

But where did all of this start? That’s what we’ll be examining: from the development of the PC to its Launch in the early ’80s, as it fought off giants such as Apple, as it was cloned by countless manufacturers, and as it eventually went 32-bit. We’LL Look at the ’90s and the start of the multimedia age, the war between the chip makers, and the establishment of Windows as the world’s Leading operating system. Lastly, we’LL examine the new millennium, initially dominated by Microsoft and the PC, followed by a slow shift to where we are now.

But before we go anywhere, to understand the revolutionary nature of the PC, you first need to grasp who IBM was at the time, and the culture that surrounded it.

THE LEAD UP TO THE PC

For decades, IBM was king, but the late 1970s brought a change in direction.

IBM WAS FORMED in the early 20th century by people who invented the kind of punch-card machines and tabulators that revolutionized the previous century. IBM introduced big data to the US government, with its equipment keeping track of millions of employment records in the 1930s. It gave us magnetic swipe cards, the hard disk, the floppy disk, and even ATMs. It would develop the first demonstration of AI, and be integral to NASA space programs. IBM has employed five Nobel Prize winners, six Turing Award recipients, and is one of the world’s largest employers.

When it came to respected marques, you couldn’t get much higher than IBM, and the top brass knew it—to say the corporate culture was stuffy would be an understatement. Company pride and loyalty was instilled in all workers. IBM bosses insisted on well-groomed salesmen, with dark suits, white shirts, and “sincere” ties—there was even an IBM anthem and songbook. IBM’s mainframe computers dominated the ’60s and ’70s, and that grip on the industry gave IBM an almost instant association with computers in the minds of American consumers. But trouble was on the horizon.

Who made the first computer

The late ’70s were saturated by “microcomputers” from the likes of Apple, Commodore, Atari, and Tandy. IBM was losing customers as giant mainframes made way for microcomputers. As similarly large manufacturers were about to launch micros of their own, trying a new form of desktop computer was a way to fight back against rivals, but it would take a monumental shift in strategy.

IBM took years to develop anything, with endless layers of bureaucracy, testing every detail before releasing anything to market. Its chief business in the ’60s was huge mainframes that filled entire floors of a building, and took squads of people to run, while on the world.

At last, the PC, the IBM 5150, is ready to take the so-called “minicomputers” of mid-’60s and ’70s were still the size of a refrigerator.

IBM was a long way from offering simple and (relatively) affordable desktop computers, and didn’t even have experience with retail stores. Meanwhile, microcomputer manufacturers were developing new models in months, and there was no way IBM could keep up while sticking to traditional methods.

ASSEMBLING THE CREW

In August 1979, the heads of IBM met to discuss the growing threat of microcomputers, and their need to develop a personal computer in retaliation. IBM president John Opel already recognized the potential in personal computers, but could also see the weakness in IBM’s existing methods. In order to encourage innovation, IBM created a series of Independent Business Units, which were given a level of autonomy. One of these would soon be led by executive Bill Lowe, who would become the father of the PC.

In 1980, Lowe promised he could turn out a model within a year if he wasn’t constrained by IBM’s methods. Lowe’s initial research led him to Atari, which was keen to work for IBM as an OEM builder, proposing a machine based on the Atari 800 line. Lowe suggested IBM should acquire Atari, but IBM rejected the idea in favor of developing a new IBM model instead. This model was to be developed within the year, with Lowe given an

Desktop Predecessors – first ever computer

Contrary to popular belief, the IBM PC was not the first personal computer, nor was it the first desktop computer by IBM. Microcomputers existed long before “the PC,” and as for IBM itself, desktop computers had already been developed, though in very different forms to the PC we know now.

When was the first computer made ?

When was the first computer made? In 1973, IBM developed a prototype computer called SCAMP, which emulated an IBM 1130 minicomputer in a “portable” (we use the term loosely) boxed form factor, with a small monitor and keyboard built in.

Perhaps of most interest in relation to the 5150 Personal Computer is 1975’s IBM PC 5100. Before you start jumping up and down, here the “PC” actually stands for “Portable Computer.” This was similar to the SCAMP, but designed for mass manufacture, using an IBM PALM CPU. A good 64KB model cost just under $20,000, and that’s in 1975 money.

Finally, there’s IBM’s System/23 Datamaster, released just before the PC.

This was a definite desktop computer, with a relatively compact footprint, but it ran an 8-bit Intel 8085 CPU, and had two 8-inch floppy drives. Interestingly, the System/23 used the new Model F keyboard before the PC.

independent team. This new squad, the Dirty Dozen, a group of IBM misfits, was allowed to do things however they saw fit to get the job done. The task was code-named Project Chess, with Lowe promising a working prototype in 30 days.

After talking to potential dealers, Lowe went for an open architecture. While dealers were very interested in an IBM machine, it just wouldn’t work if they had to operate within IBM’s proprietary methods. If dealers were going to repair these machines, they needed to be made from standard off-the-shelf parts.

By August, Lowe had a very basic prototype and a business plan that broke away from established IBM practice. Based on this new open architecture, the PC would use standard components and software, instead of IBM parts, and be sold via normal retail channels.

DEVELOPING THE PC – development of computer

Over the coming months, the Dirty Dozen grew exponentially in number and toiled away to transform the prototype into a world-class machine. They focused on giving the PC an excellent keyboard, which they delivered with the IBM Model F.

It needed to be durable and reliable, so each key was rated to 100 million keystrokes. It also needed to be tactile and ergonomic. IBM was renowned for quality keyboards, and would try to replicate the feel of older beamspring terminal keyboards with a new Buckling Spring technology.

These gave the keyboards the famous clacky sound and weighted feel that was popular with typists, giving a tactile feedback unrivaled at the time. The PC’s keyboard alone would become the main selling point for a lot of customers, and IBM keyboards would be the best in the business for the next two decades.

Next, the crew turned to the CPU. IBM’s own 801 RISC processor was considered (which would have been significantly more powerful), but for convenience and compatibility’s sake, the team chose the Intel 8088.

By choosing an 8088 processor, technically the original IBM PC is only partly 16-bit. There is often confusion over why IBM chose to use the inferior 8088 CPU instead of the 8086 (especially with a so-called “x86” computer). Both are internally 16-bit, but the difference between

IBM wasn’t just a colossus in size, but also in sluggishness. Observers claimed it would take “nine months to ship an empty box.”

the 8086 and the 8088 was the data path—the 8086 had a full 16-bit data path; the 8088’s was 8-bit.

The 8088 was still quite fast, but was cheaper and could be bought in the large quantities the new PC market would demand. An 8086 would also require far more complex and expensive motherboards, and may not have been able to be produced in sufficient numbers to keep up with demand. A lot of the hardware likely to be used in the PC also had an 8-bit bus, so an 8088 would be better for compatibility.

As for the motherboard, RAM would be expandable up to 256KB, an optional 8087 math coprocessor would be available, and there would be five ISA expansion slots. Putting the machine together, launch models would have a choice of 16 or 64KB of RAM, space for two 5.25-inch floppy disk drives, and a cassette jack for tape storage. Buyers had a choice of monochrome or CGA graphics, and the Intel 8088 powering the system would be running at 4.77MHz.

With the hardware sorted, the burden of developing the operating system would be largely outsourced to Microsoft, with IBM offering consumers the joint-venture PC DOS. The final machine was dubbed the IBM Model Number 5150. This moniker would be immediately forgotten, for in the minds of the press, it was really IBM’s Personal Computer that was about to launch.

Apple II

The great rival

Without the Apple II, it’s possible the PC would never have existed. Although a subject of debate, it’s generally agreed that the Apple II was a primary influence on the PC. Many IBM engineers owned one—as did many customers, who found that they could easily do jobs, such as working on spreadsheets, that were nearly impossible on a giant mainframe.

Sporting an 8-bit MOS 6502 processor, with between 4KB and 64KB of RAM, it debuted in June 1977 for a base price of $1,298. It had an incredible production run, selling from 1977 to 1993. Developed by Steve Wozniak, the Apple II stands in stark contrast to

products developed by Apple’s lesser Steve (Mr. Jobs). Chiefly, the Apple II is designed around an open architecture, with a removable lid allowing easy access to the motherboard and expansion slots. Much like the PC, the Apple II would be the subject of numerous clones over the years.

Even though the PC was newer, the Apple II retained advantages over the PC, such as having eight expansion slots over the PC’s five, and much more convenient gaming, with bundled joysticks and games that loaded in seconds.

An open architecture? Easy access to expansion slots? Steve Jobs could never have designed such a thing!

THE 1980s: THE PC OFFICIALLY LAUNCHES

Rivals were unfazed by the old timer’s new machine, but had no idea what was about to hit them

AFTER A 12-month development, IBM announced its new Personal Computer on August 12, 1981. The $1,565 base model included 16KB of RAM, CGA graphics, and an input jack, relying on the user to provide a cassette deck (disk drives were optional and far more expensive).

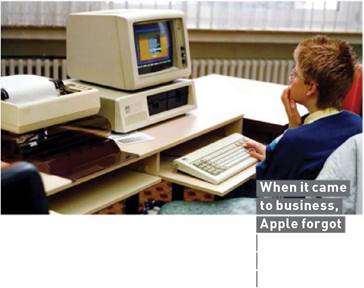

Rivals such as RadioShack and Apple were unconcerned, as they had many times more dealers, large support networks, extensive software libraries, cheaper products, and models with better performance. Steve Jobs bought one to dissect and was unimpressed by some of its old-fashioned tech. In its hubris, Apple took out a full-page ad proclaiming “Welcome, IBM. Seriously.” But it failed to recognize the weight a company like IBM carried with businesses.

Even though IBM’s product was inferior in many ways to its cheaper competitors, businesses saw

IBM as a safe bet, with excellent customer support. Within a year, the PC overtook the Apple II as the best-selling desktop computer. In 1983, two thirds of corporate customers standardized on the PC as their computer of choice, with only nine percent choosing Apple, and by 1984, the PC’s annual revenue had doubled Apple’s.

IBM surprised the industry by breaking its own traditions. Not only did it allow service training for non- IBM personnel, but it published the PC’s tech specs and schematics to encourage third-party peripherals and software. Within a couple of years, the PC was the new standard for desktop computers, spawning a massive sub-industry of peripherals and expansions.

In 1982, the PC was updated to IBM’s XT

The Compaq Portable made waves as the first proper IBM- compatible. If you could lift it.

A 386 with VGA—ask someone to think of classic DOS gaming, and this is likely the first thing that comes to mind.

(extended Technology) standard, removing the cassette jack, and adding a 10MB hard disk. It was the first PC with a hard disk as standard.

August 1984 brought IBM’s next major release, the PC/AT (Advanced Technology). Sporting a 6MHz Intel 80286 (aka 286—no one used the “80” prefix anymore), it came with 256KB of RAM, expandable up to 16MB. Initial models were limited to CGA and monochrome, but IBM’s new 16-color EGA standard was soon introduced, allowing for 16 colors at 640×350. This was another step toward the PC we recognize now, with things like standardized drive bays, motherboard mounting points, and the basic keyboard layout we now take for granted.

THE IBM-COMPATIBLES

Although a hit with businesses, the first PC was too expensive for home users. The base model’s price wasn’t too outlandish, but it didn’t include a monitor or floppy drive—a decent 64KB model

PCjr

The PCjr looked promising: an Intel 8088 CPU, CGA Plus graphics, and the kind of sound chips used by Sega consoles. IBM promised a home machine with PC compatibility, improved graphics and sound, and a lower price of

$1,269. Consumers adored the wireless keyboard, and it was IBM, the king of computing. Pundits thought the PCjr would destroy the competition, but on release it was universally panned.

A Commodore 64 was a third of the price, faster, with better graphics, and a huge software library. The PCjr’s

strange hardware and optimizations also meant it was only partially PC compatible, failing gamers and business users alike. What really riled consumers was the appalling rubber chiclet keyboard: A relatively expensive computer—from a company known for quality keyboards— was lumbered with

something found on $99 budget micros.

Initial sales were a disaster, but a campaign of discounts, ads, and upgrades (particularly the keyboard) turned things around, making the PCjr a mild success. Nevertheless, its reputation was damaged—the PCjr was canceled in 1985.

with a floppy drive and monitor was more than $3,000 (over $8,000 in today’s money). Rivals smelled opportunity, and with an open architecture, it wouldn’t be long before IBM clones would arrive.

Initially IBM wasn’t concerned: While a PC could be mostly replicated with retail parts, the BIOS belonged to IBM, which guaranteed proper IBM compatibility. However, companies such as Award and American Megatrends reverse engineered IBM’s BIOS, and companies such as Dell, Compaq, and HP then used cloned BIOSes to build clone machines.

The first clone came from Columbia Data Products with 1982’s MPC 1600, but 1983 saw the landmark Compaq Portable, the first computer to be almost fully IBM compatible. Compaq used its own BIOS and provided a very different form factor to a desktop PC, with all the components in one box, including a small CRT monitor.

When IBM released its ill-fated budget PCjr in 1984, RadioShack made a clone, the Tandy 1000. It was far more successful than the PCjr, with better PC compatibility. After the PCjr’s cancelation, existing software and peripherals came to be associated with the Tandy.

Far cheaper clones were eroding IBM’s control of the market, with its share dropping from 76 percent in 1983 to 26 percent in 1986.

ENTER THE 386

At least IBM had the technological lead, but even that would be eroded when Compaq released 1986’s Deskpro 386. Intel had recently released its 32-bit 80386 CPU, but unfortunately for IBM, Compaq beat it to market with a 386 machine boasting 1MB of RAM and MS-DOS 3.1. This was two to five times faster than a 286, with a base price of $6,500. Compaq’s machines were the very top of the line, and would steal IBM’s title of business leader.

IBM fought back with 1987’s Personal System/2 (PS/2), finally releasing a 386 to market; the most powerful model sporting a 20MHz CPU, 2MB of RAM, and a 115MB hard disk. This was a landmark computer, standardizing on things such as a 1.44MB 3.5-inch floppy, and the PS/2 ports still used by mice and keyboards. However, the biggest leap was in the introduction

of VGA graphics. On the desktop, this meant 640×480 in 16 colors, and a low-res mode of 320×200 in 256 colors, popular for gaming.

Despite the incredible advances, IBM continued to lose ground to the clones. Although the PS/2 line sold well for a time, IBM’s machines were still too expensive for the general public. As the ’80s progressed, the name “PC” started losing its association with IBM, and the public started referring instead to “IBM-compatibles.”

Although the PC was sweeping America, in many regions worldwide micros were still wildly popular— Europe was particularly enamored of the Atari ST and Commodore Amiga. Where PCs were lacking in the GUI stakes, these Motorola 68000-based machines already had sophisticated GUIs and astonishing multimedia capabilities that would trounce PCs for some years—often at a fraction of the cost.

Nevertheless, the PC continued to grow and develop, with further advancements such as 800×600 SVGA (Super VGA) graphics in 1988. And the ’80s had one last trick up their sleeve: In April 1989, Intel released the 486, the powerhouse CPU that would kick-start the next decade. The first computer to ship was IBM’s 486/25 Power Platform in October, making it the most powerful machine on the market.

However, 486 machines wouldn’t enter most households until the 1990s—286s were still the order of the day, and many brands were still making budget XT clones. Where a 386 was considered the height of sophistication, a 486 was witchcraft. Nevertheless, the ’80s were a time of astonishing technological progress: We entered the decade with 8-bit micros and left with full 32-bit processors and SVGA graphics. It’s unlikely such rapid progress will be repeated.

the adage, “No one ever

The OS Wars Begin

The battle for which company and OS will rule the PC starts with the beginning of the PC itself. Mention “DOS” and Microsoft DOS will come to mind, but there are plenty of variants. Enter Digital Research’s CP/M-86. CP/M was the original “DOS,” shipped with most non-proprietary machines. IBM originally planned to use CP/ M-86 with the PC, but negotiations went sour when IBM wanted to pay Digital Research a one-time fee, rather than on-going royalties.

Meanwhile, Microsoft had purchased a clone of CP/M-86 from Seattle Computer Products, 86-DOS (aka QDOS—Quick and Dirty Operating System). This was re-branded to MS-DOS and IBM’s PC DOS, available for the PC. After Digital Research threatened legal action, IBM gave customers the option to buy either CP/M-86 or MS-DOS/PC DOS. MS-DOS/PC DOS was the substantially cheaper option, and outsold CP/M-86 in overwhelming numbers.

IBM and Microsoft’s MS-DOS/ PC DOS partnership wouldn’t last long, with the two products gradually diverging over the years, with different features and compatibility. PC DOS was designed for genuine IBM hardware, and as IBM compatibles took over the market, the more generic MS-DOS would become ubiquitous. Regardless, both versions would stay in production until the turn of the century.

IBM’s PC DOS “By Microsoft” partnership didn’t last long.

THE 32-BIT ’90s

A decade when computers would adopt desktops and multimedia

PREVIOUS VERSIONS of Windows were unsuccessful, but with 1990’s Windows 3.0, the PC desktop was seen as a viable alternative to the Macintosh and Amiga. Windows 3.0 had a new interface, multitasking abilities, and mouse-driven productivity suites that freed users from the command line.

Meanwhile, IBM’s OS/2 had been trying to establish itself as the respectable GUI for corporate America. By 1990, the alliance between IBM and Microsoft had essentially finished, with the two becoming rivals. Although newer versions of OS/2 would be more advanced, for now Microsoft had the technological advantage.

IBM was still hampered by 286 machines, keeping OS/2 primarily 16-bit, unable to use the advanced features of the 386.

April 1992 finally saw OS/2 become 32-bit. In most ways, it was superior, with extensions to DOS, and Windows 3.x support in a stable environment. But while Windows targeted clone machines, OS/2 targeted IBM hardware, so it couldn’t run on many clones where Windows ran perfectly. Furthermore, while IBM sold OS/2 as a separate product, Microsoft bundled Windows with new PCs.

Microsoft’s dominance started with Windows for Workgroups 3.11 in August 1993. It had new 32-bit capabilities and proper networking. It devoured the business space, and 3.11 would be the environment many people grew up with.

THE MULTIMEDIA AGE

In the mid-’90s, every PC had a soundcard, CD-ROM drive, and

A typical ’90s gaming PC, where a 3D accelerator would make you the envy of all n00bs.

tinny set of multimedia speakers. CD-ROM’s 650MB of storage allowed more expansive gaming, with FMV cutscenes and CD-audio soundtracks. Schools bought edutainment packages with archived video and interactivity.

By now, the 486 was standard. Although 386s were still functional business machines, you needed a 486 to enjoy this era. Thankfully, hardware prices fell dramatically; while ’80s PCs usually had Intel CPUs, rival manufacturers were on the ascent and lowering costs.

Although AMD CPUs were often from a previous generation to Intel’s, its chips were more efficient and allowed higher clock speeds, giving similar performance at much lower prices. Cyrix was making a name for itself with 486-upgrade processors, providing a cheap upgrade route for 386 owners with a new CPU in their old motherboard.

1993’s Intel Pentium brought the next generation of CPUs. Intel dropped the “86” to differentiate itself from other manufacturers, with “Pent” coming from the Greek

“penta,” meaning five (implying a 586 without saying it).

The Pentium gave almost twice the performance per clock cycle as the 486, but early Pentiums were only 50-66MHz. Meanwhile, AMD was pumping out insanely overclocked 486s, such as the DX4-120 running at 120MHz, nearly matching early Pentiums. AMD’s strong performance and low prices attracted manufacturers such as Acer and Compaq, whereas Cyrix’s efficient designs caught IBM’s eye, starting a partnership in 1994.

1995 saw the introduction of the ATX standard we use today, defining new mounting placements and features like automatic shutdowns. Unlike XT and AT, this change was brought by Intel instead of IBM.

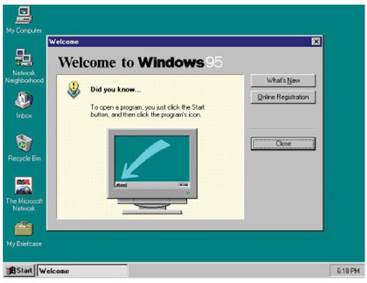

August 1995 would see the biggest change to the computing landscape yet: Windows 95. On the technical side, Windows 95 was designed around 32-bit pre-emptive multitasking, compatibility with existing DOS and Windows programs, and new tech such as DirectX and Plug and Play support. But the real change was the interface. A taskbar, a “Start” button in the bottom-left, the “Maximize,” “Minimize,” and “Close” buttons at the top-right of the window…. We take these norms for granted now, but they started with Windows 95.

Windows 95 truly established the Microsoft goliath. Computing had become mainstream, and Microsoft was a household name. It was over for competitors: Commodore had gone bankrupt, Atari hit the wall, and Apple was barely surviving. IBM still had OS/2, with its newer Warp release from a year prior, but this

The 386 and the 32-Bit Era

It’s difficult to overstate the 386’s importance. In short, the 32-bit 386 is where modern computing began. List the features of a modern OS, and for the PC, these abilities started with the 386, serving as the basis and minimum spec for

the next generation of OSes in the ’90s.

With the 386, PC operating systems immediately became more advanced, with a flood of Unix variants being ported to the platform. Advanced computing was previously dominated by

expensive Unix workstations, but once the PC went 32-bit, they grew redundant, and big Unix companies such as DEC and Sun Microsystems started falling away. Until late 2012, a 386 could still run Linux (now it requires a decadent 486).

Put a squeaky millennial in front of a 16-bit machine and they won’t know what they’re “ looking at, but with a 386, they might stand a chance.

only supported Win 3.x applications and sank into irrelevancy.

When Windows 98 arrived, it fixed many of the teething problems of Win 95, with a more stable system, better hardware support, and UI enhancements. This was also when the anti-trust lawsuits began, as Microsoft bundled Internet Explorer with Windows, itself already bundled with new computers. Now Microsoft would dominate not just PCs, but Internet browsers too.

THE PERFORMANCE AGE

3D accelerator cards—such as 3dfx’s Voodoo 2, Nvidia’s Riva TNT, and ATI’s Rage series—would be a defining feature of the late ’90s. 3D acceleration brought a new era of PC gaming. Where previous games relied on the CPU for all rendering, these new graphics cards added a GPU (graphics processing unit), which took the graphical processing burden away from the CPU, allowing substantially faster gaming and stunning graphical effects.

Although 3dfx tried to corner the market with its proprietary Glide API, it eventually lost out to competitors who used market standards such as DirectX and Silicon Graphics’s OpenGL. The ultimate card of the ’90s would be 1999’s Nvidia GeForce 256.

This point is where the CPU race is whittled down to AMD and Intel.

Until now, things looked great for Cyrix. The mid-’90s saw 5×86 upgrade chips for 486 machines, followed by the 6×86 in October 1995. The 6×86 out-performed mid-level Pentium machines for less money—Cyrix was becoming a technological leader rather than just a budget manufacturer.

Business was good until complex 3D games such as Quake uncovered

Other than the dull colors, Windows 95 is where the PC started to resemble the interface of today.

struggling to

sell desktop

with its new ultra-rugged ThinkPad

Cyrix’s embarrassing floating point and integer performance. Cyrix was great at spreadsheets, but terrible at gaming, which tarnished the brand. 1997’s MediaGX helped improve things, with a system-on- chip design perfect for laptops and the budget PC market, but as Intel continued to advance, Cyrix did not.

Newer-generation CPUs were really highly overclocked 6x86s— prone to high failure rates, still poor at gaming. The Cyrix-IBM partnership ended in 1998, and worse yet, Intel soon entered the budget market with its Celeron line. Cyrix was out of cash, and its tech was bought out by VIA in 1999, who gradually phased out the brand.

AMD, meanwhile, went from strength to strength. During the Pentium era, reverse-engineering Intel’s processors became too complex, so AMD started designing its own style of processors, rather than follow Intel designs.

In 1996, AMD released the K5, the first Pentium rival, but 1997 brought true success with the K6. This was a proper rival to the new Pentium II, but could work in older Socket 7 motherboards. The K6 series was wildly successful, with its famous 3DNow! instructions, and cheaper prices. The successive K6-2 and K6-3 chips continued to rival advancing Pentium II and III models, and would eventually dominate most of the sub-$1,000 market.

We would end the decade with 1999’s K7 Athlon, the first retail CPU to break the 1GHz mark.

The ’90s were a time of survival of the fittest, ending with one dominant OS and two CPU makers. Thankfully, the GPU market still had a few years of diversity remaining.

BeOS – The sleek alternative

Be Inc. (founded by ex-Apple executive Frenchman Jean- Louis Gassee) launched the BeBox in October 1995, running its own operating system, BeOS. Optimized around multimedia performance for the masses, BeOS was intended to compete with both Mac OS and Windows. Lightning fast and free of the legacies of old 16-bit hardware, BeOS had features such as symmetric multiprocessing for multi- CPU machines, pre-emptive multitasking, and the 64-bit journaled file system BFS.

Although the BeBox itself was unsuccessful, BeOS was ported to the Macintosh in 1996, and almost became the new system to replace Mac OS. Gassee’s $300 million asking price was too steep, however, and Apple went with Steve Jobs’s NeXTSTEP OS instead. BeOS was then ported to the PC in 1998, along with a free stripped-down BeOS 5.0 Personal Edition, but it failed to gain more than a niche audience (Microsoft may also have worked against its adoption).

Be Inc. was bought out by Palm Inc. in 2001.

Despite numerous recreations, BeOS is now survived by Haiku, a popular open-source re-implementation with BeOS binary compatibility on 32-bit versions.

In an alternate universe of Betamax VCRs, where Al Gore was president, BeOS reigns across Macs and PCs.

BEYOND 2000

Microsoft totally dominates the start of the millennium, but this decade ends elsewhere

THE NEW CENTURY

Windows 2000 (arguably the best release of Windows) and Windows Me (arguably the worst). Win 2000 was based on Microsoft’s NT platform, finally moving Windows away from DOS, while remaining mostly backward compatible with Windows 9x and DOS programs. 2000 had the stability of NT and the minimal aesthetic of the 9x series, without the bloat of future releases.

Later in the year, Microsoft released Windows Me (Millennium Edition)—still based on Windows 9x, which was still based on DOS. Often regarded as Microsoft’s worst operating system, it somehow managed to be buggier and less refined than previous 9x releases. Whereas Windows 2000 is remembered as an underrated gem, Windows Me brings cold shivers down the spines of IT staff who lived through that scary time.

October 2001 saw the release of Windows XP, using the same NT base as 2000, with a revamped interface, and improved multimedia capabilities. While previous versions of Windows were pretty drab, XP was colorful. XP made piracy much harder, being the first Windows to have an activation scheme. The mix of relative stability and a friendly GUI made XP one of the most popular OSes of all time. Microsoft kept having to extend support for XP, right up until 2014, when it officially cut the cord. Despite this, there are still plenty of

After 2007’s iPhone, Apple shifted industry focus to portable devices, becoming the world’s biggest company in 2012.

XP users, spreading digital disease across the Internet.

PLATFORM SHAKE-UPS

In April 2003, AMD released its 64- bit Opteron processor. This was the first major change to the x86 platform not made by Intel, and would be labeled either x86-64 or, embarrassingly for Intel, AMD64. Intel was forced into the position of modifying its processors for software compatibility with AMD’s new specification. Although it would take a few years for the new spec to catch on, it would eventually become the standard in use today.

In May 2005, IBM sold its PC division to Lenovo in a deal worth nearly $2 billion. As part of the deal, IBM would acquire a stake in Lenovo, and sell Lenovo goods under a marketing alliance— existing lines like the famous IBM ThinkPad laptops would be sold

as Lenovo ThinkPads. Skepticism was high over the viability of such a merger but Lenovo went on to become the biggest PC vendor in the world, while IBM would focus on big-data markets and the cloud.

In June 2005, Apple announced that Macs would switch from PowerPC to x86 processors. Steve Jobs was disappointed in the progress of PowerPC CPUs, which were slower than Apple had promised consumers, too hot for laptops, and consumed too much power. Although the market was concerned, the Intel machines were faster than their PowerPC counterparts, and sales increased.

Between July and October 2006, AMD bought out graphics company ATI Technologies in a deal worth $5.6 billion. Merging ATI’s graphics tech with its existing CPU know-how, AMD was now taking on the might of both Intel and Nvidia with

The Raspberry Pi Revolution

In February 2012, the successful Raspberry Pi was released, taking the industry by storm with a new form factor, often referred to as a single board computer (SBC). Made in Britain from a combination of cell phone and desktop parts, the Pi is barely larger than a credit card, for $35. The Pi was intended to get kids programming

after the Raspberry Pi Foundation recognized a national decrease in programming skills, but it became more popular with hobby builders and the embedded computing industry.

Unfortunately for PC giants, the Pi ran Linux on an ARM CPU instead of Windows on x86. Due to its popularity, Microsoft ported Windows to the system a few

years later, and manufacturers started producing rival machines. For the ARM crowd, there are products like the Asus Tinker Boards or Pine 64’s RockPro64. For the x86 crowd, there are

products like the Atomic Pi and the LattePanda series. ARM boards are generally cheaper and more efficient, while x86 boards can often run regular builds of Windows or Linux.

In spite of imitations, the Raspberry Pi still sets the standard and has spawned] an entire cottage industry of add-ons.

To confused audiences worldwide, CEO Satya Nadella announces Linux-based Microsoft technologies.

the manufacturing strength of combined technologies.

THE VISTA HITS THE FAN

In January 2007, Windows Vista was released. Even though it was based on NT, Vista had a vastly different framework from previous versions, making for an essentially new platform. Vista was designed to be more secure, showcasing new features like intelligent RAM storage, and an updated GUI with effects like window translucency, but it was savaged by the press.

Windows Vista had bad backward compatibility, long loading times, and a stream of invasive warning messages. It improved with time, but the damage was done- computer manufacturers started shipping PCs with the option of XP. Microsoft would learn from its mistakes with the next release.

Windows 7 arrived in July 2009. Based on the same platform as Vista, it refined the codebase, bringing performance improvements, better stability, and a sensible interface.

To pick some highlights from a long list of new features, Win 7 had faster boot times, better multicore performance, easier networking, new virtualization tech, and better backward compatibility. The UI changes were popular, including a new taskbar with more functionality, and the Snap function, which moved and resized windows when dragged against the screen edges.

Windows 7 would become the fastest selling OS in history, and around a third of PCs still use it. It’s well regarded among IT staff, and many users are avoiding the switch to Windows 10, despite Extended Support ending next year.

In July 2012, Google’s Chrome browser overtook Internet Explorer in usage share, and by April 2013,

both Chrome and Firefox had a greater share of users than Internet Explorer, ending Microsoft’s dominance of the browser market.

In October 2012, Windows 8 was released. Despite Microsoft’s attempts to innovate, Windows 8 was critically savaged. As mobile devices were overtaking traditional desktops, Win 8 tried to have more of a “touch” interface, removing the “Start” button, and switching to a tile-based design. The result was a dreadful unintuitive compromise. Win 8 also introduced the Windows Store, a Microsoft-governed system for buying apps, in the style of Apple. This restrictive way of buying software drew criticism, especially from Valve, who started its own SteamOS in response.

Windows 8.1 addressed many of its criticisms, chiefly by bringing back the “Start” button and allowing users to boot a traditional desktop. But again, the damage was done. While Windows 7 is still in heavy use, Windows 8 is almost forgotten.

WHERE ARE WE NOW?

We end the decade with Windows 10 (released July 2015). Reception has been mixed. On the plus side, the interface is a more functional blend of Windows 7’s traditional GUI and Windows 8’s tile system, and Windows finally has virtual desktops (something featured in other OSes for decades). On the down side, forced system updates continue to infuriate users, there is a worrying amount of data collection, and the Microsoft Store undermines the open nature of the PC platform.

Microsoft still dominates the PC desktop, but is no longer a monopoly, with Apple having spent most of the decade wealthier than Microsoft. Niche OSes are growing in popularity. Linux is creeping into

After Vista was poorly received, Microsoft won back consumer confidence with 2009’s Windows 7.

everything from DVD players to the world’s supercomputers. Microsoft has gone from calling Linux “a cancer” to proclaiming “Microsoft loves Linux,” shipping Windows with a Linux kernel, and running its own Azure Sphere Linux distribution for IoT devices.

To focus on the PC, it isn’t the dominant format it once was. IBM has long since left the market it created, and wisely so. Computing is more varied and takes many forms, from iPads to smartphones, from Chromebooks to weird Android devices no one can categorize. Computing has returned to a diversity like the ’80s, but the PC no longer has the same supremacy— nor do the giants that established it, such as IBM, Intel, and Microsoft.

What About SteamOS?

When Microsoft released its proprietary Windows Store, Valve’s Gabe Newell described it as a “catastrophe for everyone in the PC space.” Valve felt that the Windows Store threatened Steam’s existence, and decided to branch out with its own platform, using Linux as a base. First, Valve released the full Steam gaming client for Linux in February 2013, followed by its own platform, SteamOS, based on Debian Linux in December 2013. (Linux and SteamOS applications are generally cross-compatible.) However, SteamOS failed to gain much traction, and most of the user base would come from the regular Linux client.

Perhaps following the advice of id Software’s John Carmack, Valve re-focused its attention from encouraging native SteamOS/Linux ports to perfecting Wine, the Windows compatibility layer for Linux. In August 2018, Valve released Proton, a modified version of Wine with a DXVK translation layer to convert between newer Direct3D system calls and Vulkan. It should be noted that Proton can be used for regular apps, not just gaming, so the more obscure games that can run, the more likely it will run any Windows apps without problems. Over half of all Windows games run out of the box, and that rate is growing steadily.

Lots of edits have been made resulting in paragraphs being split with sentences breaking mid word, and then continuing further down the page in a different section of the article. this is confusing and needs a re-edit.

otherwise a very informitave summary of the subject.