12 things we miss about old computers

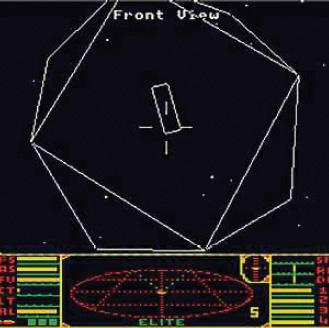

Contrast the wireframes of Elite with the lifelike realism of 2020’s Flight Simulator and you might wonder if the old world of computing is worth a second glance. But that’s not to say we can’t reflect on the past and reminisce on some of the things that have been and gone.

In fact, there are plenty of things we – and developers in particular – can learn from the nascent days of computing. Here are 12 things worth celebrating, and remembering, including thoughts from people who helped to make it all happen.

1 So many models to choose from

The dawn of the home computer in the late 1970s felt rather adventurous. Companies new and old looked to introduce millions of people to their magical machines and, in doing so, brought about a change in how people perceived computers.

Suddenly, thanks to the dawn of the microchip, they were no longer taking up entire rooms or priced so high that even major organisations could only afford to have just one. They would help you write letters, organise your finances and even entertain you.

What caught our imagination the most, though, was ongoing innovation from the likes of Acorn, Apple, APF Electronics, Apricot, Atari and Amstrad, as well as Commodore, Dragon Data, Exidy, Franklin, Fujistu, Mattel, Memotech, Radio Shack, Oric, Texas Instruments and Sinclair Research. And those were just the companies that sprang to my mind.

Models would come to market with their own operating systems, striking designs and transformative features. The trick was to avoid laying your pounds on a dud, since computers could leave the market just as quickly.

Still, who could forget the impact of the Commodore 64’s sophisticated SID sound chip that included features more commonly found in music keyboards? Or the Macintosh 128K, the first successful computer to boast a graphical user interface? Or the Amiga with its multitasking operating system?

And that’s without considering the plethora of quirky hardware add-ons and upgrades from Romantic Robot’s Multiface, which could save (and copy) games to the Dayna MacCharlie that allowed PC-compatible software to run on a Mac. Those many different ports on the back of the machines were just begging to be filled, after all.

2 Amazing feats of memory

What’s perhaps most surprising about old computers is how much developers got out of them given their small amounts of memory. The Sinclair ZX80 set the bar low with its advertised 1KB of RAM, but even when the comparatively wellendowed ZX Spectrum arrived, big challenges remained for developers.

On a Spectrum 48K, for instance, 8KB was reserved for the colours, screen and functions, while an Amstrad CPC 464 had 42KB of the 64KB available. But boy, did developers make the most of what they had.

The first word processor, for instance, Electric Pencil, was released in December 1976 for the MITS Altair – an affordable computer that had a minimum RAM of just 256 bytes. It was later released for the TRS-80, a machine that originally came with 4KB of RAM.

David Braben and Ian Bell managed to squeeze an entire universe into 22 kilobytes when they created Elite on the BBC Micro, which included a procedural generation system and 2,000 systems and planets.

The 1K ZX Chess took up just 672 bytes, which was for a long time the world’s smallest chess-playing program, until LeanChess was created just two years ago for DOS using a mind-boggling 288 bytes.

But therein lies the point. The developers of old were set the challenge of creating software with minuscule amounts of memory at their disposal and they pulled off amazing feats – something some modern-day coders are evidently seeking to emulate.

So let’s forgive Bill Gates, who is supposed to have once said “640K ought to be enough for anyone” (something he’s long denied). On past performances, he had good grounds for such an observation.

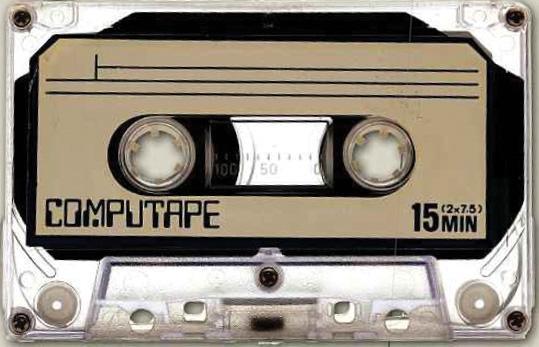

3 Those pesky tapes

Compact cassette tapes were slow and unreliable, but we miss them all the same.

Originally developed by Philips in 1962, they quickly became a popular medium for music. Then, in 1973, Hewlett Packard developed the HP 9821A computer complete with a compact cassette drive, and the technology stuck around for much of the 1980s as a relatively inexpensive way to load and save data (the earliest IBM PC in August 1981 had a cassette drive for storage).

Anyone who used tapes would be greeted by a screeching, piercing sound, since the data was represented as audio. Sometimes they would fail, forcing you to rewind the tape. Other times, they would spill their contents, requiring you to grab a pencil to spool it back in.

Even so, we persevered, tearing tapes from magazine covers or picking up budget games for a couple of pounds at Boots. We’d be eager to see what goodies awaited on those ferric oxide-coated magnetic strips and, for many, the words “Press play on tape” became etched into the mind (particularly if you had a multi-load game on the go where each level had to be ingested separately).

Not that cassettes had the market to themselves. Although floppy disks were invented in 1971 by IBM engineers and came in various sizes (3.5in being most popular), Sinclair Research fruitlessly bet big on its 1.3in-wide ZX Microdrive cartridges in 1983, packing a 5m endless loop of magnetic tape. There were even two mid-80s consoles – Control-Vision and Action Max – that used VHS tapes.

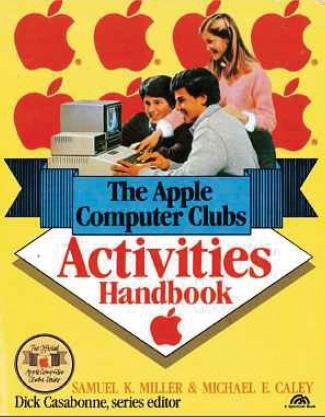

4 Computer clubs and user groups

You’ve likely heard of the Homebrew Computer Club, which ran in California for nine years from 5 March 1975 and counted the likes of Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak among its members. It was at one of these meetings that the single-board, 4KB Apple-1 computer – priced at $666.66 – was given its first public airing. Yet it was far from being the only computer club ever formed.

Such gatherings were common in schools, community centres and scores of dusty, smoky public house function rooms across the US, UK and elsewhere. Hobbyists would share tips, work on programs and products, create newsletters and potentially make exciting discoveries.

Some grew into national groups. The Chaos Computer Club, established in Germany in 1981, still exists today as Europe’s largest association of hackers, with 7,700 members.

What we miss most, though, are the numerous small, local groups, with many forming around the equally missed computer shops of the time. Initially wide-ranging, they began to settle around specific computers, and their value was recognised by the BBC’s Computer Literacy Project (CLP), which emerged in 1980.

“School playgrounds up and down the land played host to pirating pupils passing around copies of commercial software”

David Highton, of Broadcasting Support Services, asked readers of Personal Computer World magazine to contact him with details of their clubs, believing them to offer “hands-on experience for people who don’t want to go on a formal course”. What’s more, the CLP’s official computer, the BBC Micro, was also created by former members of the Cambridge University Processor Group, Steve Furber and Sophie Wilson, then working for Acorn.

Clubs helped to bring shape and organisation to a fledging computer scene. They also offered camaraderie, drinks and a chance for a natter.

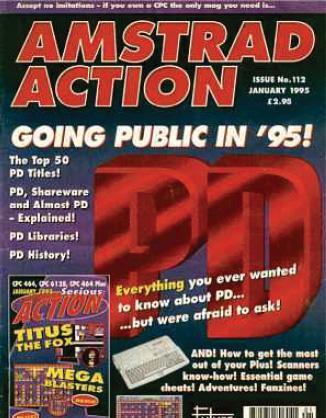

5 Public domain (PD) software

Yes, there is an abundance of free software available for download today, and without the amazing LibreOffice your correspondent would be that little bit poorer each month. But there was something exciting about the public domain software of old, primarily because of the process involved in getting your hands on it.

Although school playgrounds up and down the land would regularly play host to pirating pupils passing around copies of commercial software (mainly games), obtaining PD software tended to involve sending a stamped-addressed envelope for a badly photocopied catalogue then trying to decipher what was on offer based on the list of obscure-sounding names.

In some cases, you then had to send another SAE with a disk and a small copy fee before waiting for the floppy to return packed (hopefully) with goodies. It was a great way to build up a library of software, and among the useless filler there were some real gems, including the feature-packed DTP package PowerPage for the Amstrad CPC.

Such was PD’s popularity, Future Publishing even created a magazine called Public Domain in 1991 covering software for the Amiga, PC and Atari ST. Those were the days when newsagent shelves groaned under the weight of dozens of computer and videogame magazines, however – something else we badly miss!

For the rest of this article, we find out what industry bigwigs from the time now miss – if anything!

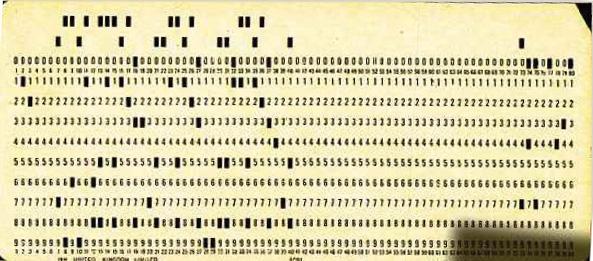

6 The first beginning

“I have an old manual typewriter that I still use,” said Bernard Luskin, former CEO of Philips Interactive Media, which published software for the CD-i. “It is like an old friend but I don’t miss anything that I can think of as computers have evolved.

“Computers are pervasive in every facet of life, including my Tesla, watch and iPhone. We have come a long way since my first LGP 30, machine language, paper tape input computer.

“Punched cards have disappeared, CDs have faded in ubiquitous use, giving way to streaming, and the world has become more complicated and simple at the same time. We are at a new beginning. But we are always at a new beginning.”

7 Turning them off and on again!

“Old computers would boot up quickly and you could just turn them off without worrying about corrupting the operating system,” said Paul Gardner-Stephen, head of the Mega-65 project to recreate an abandoned Commodore 8-bit computer. “But I think what I miss most is the simplicity and the physicality. There’s something really nice about sitting at a computer and understanding – or at least imagining – what the computer is doing, back when keyboards were real, with full travel, and maybe even with strange symbols printed on the front of the keys, rather than just on the top.”

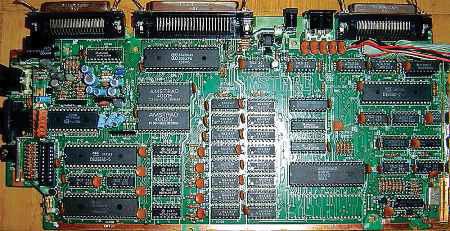

8 The DIY approach

“I guess what I miss most is being able to build things by hand, and understanding pretty much everything that was going on – every signal on the board could be seen on a scope, debugged with a logic probe, traced with a logic analyser and so on,” said Steve Furber, the computer scientist who codesigned the BBC Micro and ARM 32-bit RISC microprocessor.

“I love my M1 Mac, but could I fix it if it broke? Maybe, if I got lucky – I managed to fix an old MacBook Pro a few times by replacing the internal trackpad cable. But I would be working from internet anecdotes rather than any kind of depth of understanding.”

9 Those coloured plugs

“I desperately miss the simplicity of RCA cables with the colour-coded ‘male’ and ‘female’ connectors,” said Trip Hawkins, founder of Electronics Arts. “All by myself, I could move homes and in just a couple of minutes, set up all the computers from the 1980s, game systems and other media. For a few years I travelled with a Sega Genesis in a briefcase and could get it to work in hotel rooms and anyone’s office. It’s ungodly complicated now; we all need a great IT guy.”

10 Using your imagination

“When I think back, I wonder how the heck I ever thought a 4×4 block of black and white pixels was a zombie,” said David Perry, founder of Shiny Entertainment and former CEO of cloud-based games service Gaikai. “But I did, and I loved it. What I also remember is being blown away by each new game, and the computers being fast – it was all about perception, and I have so many memories of being amazed by what people created, yet it’s just very hard to convey that today. Nostalgia is such a powerful force, and I feel lucky to have been there and experienced the advancements as they happened.”

11 Learning to code

“The main thing with new computers – which may be slightly mitigated by the Raspberry Pi – is the general inability to write one’s own software, design and build add-on gadgets and so on,” said Roland Perry, former group technical consultant for Amstrad. Computer clubs and user magazines were one way to learn about how to do those things. But, anyway, we don’t have to miss such things – simply buy a retro computer and get on with it!”

12 Absolutely nothing

“When the Apple Computer Company was founded, I was the senior member of the group by 20 years and I was absolutely certain Steve Wozniak’s creation was exactly the right product, at exactly the right time,” said Ronald Wayne, cofounder of Apple who sold his 10% stake 12 days later for $2,300 (it would be worth $230 billion today). “But I never actually had any deep interest in that technology… my true passion has always been focused on the development of slot machines. As a consequence… I’ve never given a moment’s thought to the differences between the earliest products in the field, as compared to those of current manufacture.”