OpenMandriva Lx Review

Mandrake lives on as OpenMandriva Lx. Bruce talks to OpenMandriva Council members to find out more about this innovative distribution. By Bruce Byfield. Read our OpenMandriva Lx Review.

Long-time Linux users may recall the once popular Mandrake Linux, but, in North America, any traces of Mandrake have almost disappeared from public view. However, in Europe, the story is different. The once popular distribution has several descendants. In particular, its direct legal descendant is OpenMandriva Lx [1]. Wanting to learn more, I asked for more information on the OpenMandriva forum. Here is what I learned.

Back Story

OpenMandriva Lx’s history is complicated. Around the turn of the millennium, Mandrake Linux was a popular fork of Red Hat Linux. Mandrake quickly became one of the top half dozen commercial distributions, thanks mainly to the fact that it was one of the first to provide desktop utilities. However, Mandrake’s name conflicted with that of the Mandrake the Magician comic, and in 2005, Mandrake merged with the Con-nectiva distribution to become Mandriva SA. Mandriva was forked by Mageia Linux and ROSA Linux, but when it went into receivership in 2015, it formally transferred “a non-exclusive and irrevocable worldwide license” [2] of its intellectual property to OpenMandriva SA, an alliance of previous Mandriva contributors and people from related projects, including Unity Linux and Ark Linux. In turn, OpenMandriva became the association that has developed OpenMandriva Lx ever since. As OpenMandriva Chairman Bernhard Rosenkranzer (aka bero) explains, despite sharing common origins, OpenMandriva is completely separate from other forks.

Today, OpenMandriva is governed by its Council that oversees legal issues, public relations, and general organization and the Technical Committee that is responsible for development. Members of both are invited to join, rather than be elected, and decisions are made by consensus whenever possible. Currently OpenMandriva Lx has seven main devel-tn opers, plus a few irregular ones, as well as two mascots, Chwido and Laska. In the last year, there were 82,350 commits, according to bero.

On the one hand, the OpenMandriva home page [1] states that “our roots are in Mandrake and its traditions,” which, according to Council member rugyada, consists of the original source code, part of the initial development team, and “the idea of building an operating system that is simple enough for someone who has never seen Linux to get productive with, without dumbing it down to the point that it stops being useful to experts.”

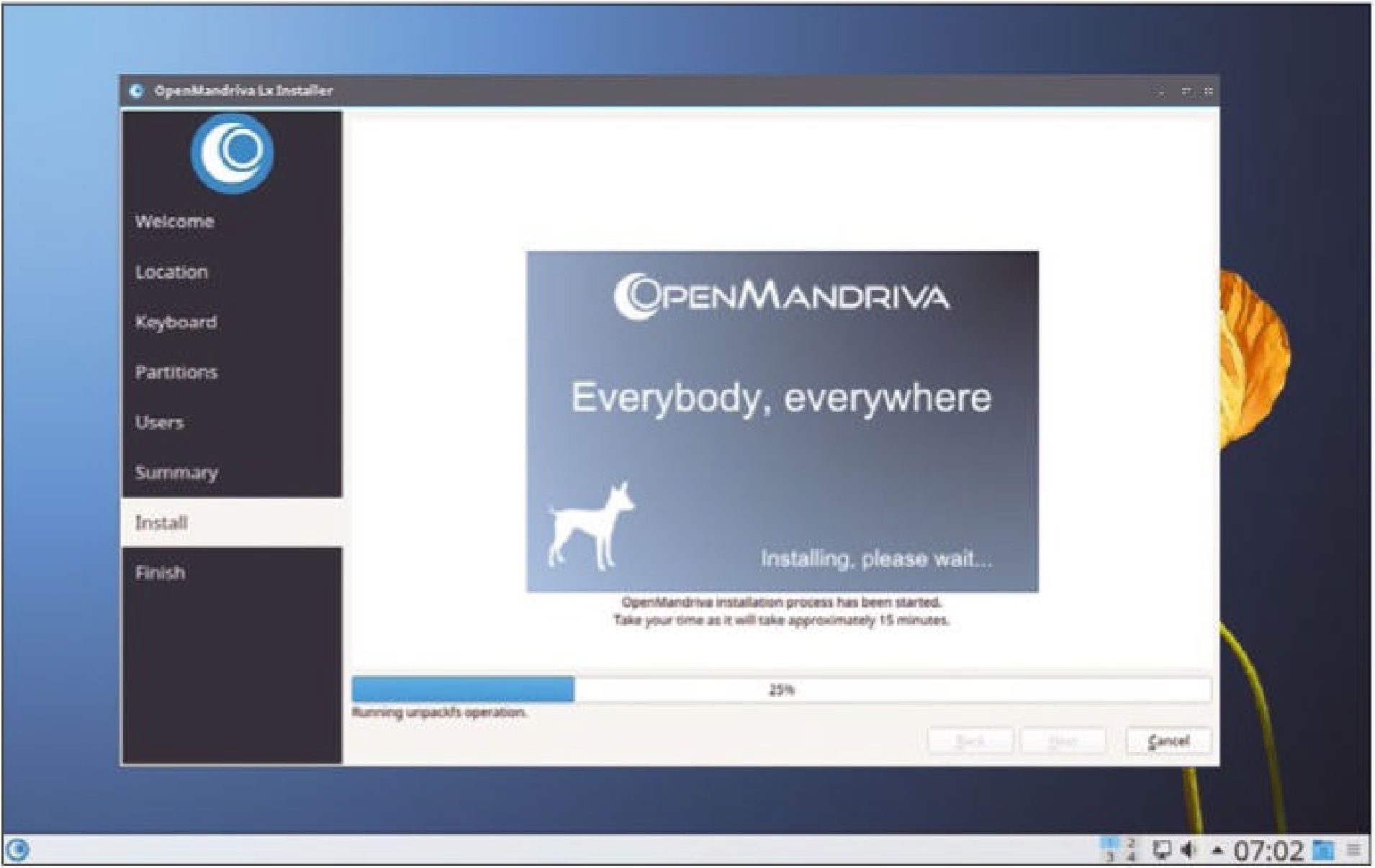

Figure 1: Like its ancestor Mandrake, OpenMandriva Lx uses its own tools for installation and administration.

On the other hand, OpenMandriva Lx has also evolved in new directions. As soon as the agreement with Mandriva SA was finalized, the distribution began to focus on new technologies. Today, most of the desktop tools have been replaced with newer ones that use different core libraries. As well, the core system has evolved, with the main toolchain being built on Clang and ported to new architectures. Currently, bero says, “we are rethinking the filesystem layout to make working across different CPU architectures easier. With qemu-static and bin-fmt, it shouldn’t be a problem to install x86-specific binaries (think Wine) on AArch64 or vice versa, or to cross-compile even packages that don’t support cross-compiling” (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 2: The OpenMandriva Lx desktop.

The Audience

For all users, OpenMandriva Lx offers both a point release (Rock) and a rolling release (ROME). As bero writes, users can choose “if they want the latest and greatest features at all times (while still getting some testing) … if they want a user experience that is essentially guaranteed not to change until they choose to update to a new point release.”

Since its early stages in 2011, Open-Mandriva’s target audience has been desktop users. For these users, OpenMandriva offers the ease of installation and a default installation “with pretty much everything we think a typical desktop user will need. You will also find a system that performs well, even on older hardware,” writes bero. Increasingly, though OpenMandriva is also aimed at developers and more experienced users, offering an up-to-date Clang toolchain, current kernels, and crosscompilers such as fiptool and github-cli.

More recently, the distribution has started to focus on server users as well. Bero writes that “we have been working with Ampere to get OMLx [OpenMandriva Lx] running on their AArch64 servers and inside cloud services running on them, such as Oracle Cloud. Here our aim is to prove that stable is spelled with a ‘b’ in the middle – and doesn’t have to imply ‘stale’. We believe a system can be stable without relying on technologies that are a few years behind the time. Of course we also support x86 servers.” In addition, “server users may well appreciate current versions of the PHP and Java stacks and always up-to-date PostgreSQL and MariaDB, our docker containers, and the performance (booting our Ampere Altra server with the preloaded CentOS took more than seven minutes -which we cut down to less than four by installing an OpenMandriva snapshot). ”

Hardware Support

Like most distributions, OpenManriva Lx supports a broad range of hardware. However, out of a wish to remain open source, the distribution recommends avoiding NVIDIA graphics, although the nouveau graphics are available. Among the supported architectures are a variety of AArch64 (ARM) and Raspberry devices, as well as Pinebook Pro or a high-end Ampere Altra server. No UEFI support is required for AArch64 devices, on the grounds that to do so would limit hardware support. Instead, OpenMandriva builds a custom image during installation.

In the near future, OpenMandriva expects some innovative support. Both a port to Pine Phone Pro and support for cheap hardware are in their early stages, and, most important, support for the open hardware RISC-V chips, suspended after problems with the first SiFive Unlimited boards, is expected to resume after the next general release using SiFive Unmatched VisionFive boards. “Even though there is currently little real world hardware available,” bero says, “RISC-V is a very interesting target to us, primarily because of its open nature. ” Although no one from OpenMandriva has said so, the distribution may well be the first to support RISC-V chips, and thus the first to permit systems in which both the software and the hardware are open.

A Tradition of Innovation

Asked what might attract users to OpenMandriva Lx, bero notes that, unlike many distros, it is not a derivative, and that “this gives us more room to be innovative and go new ways.”

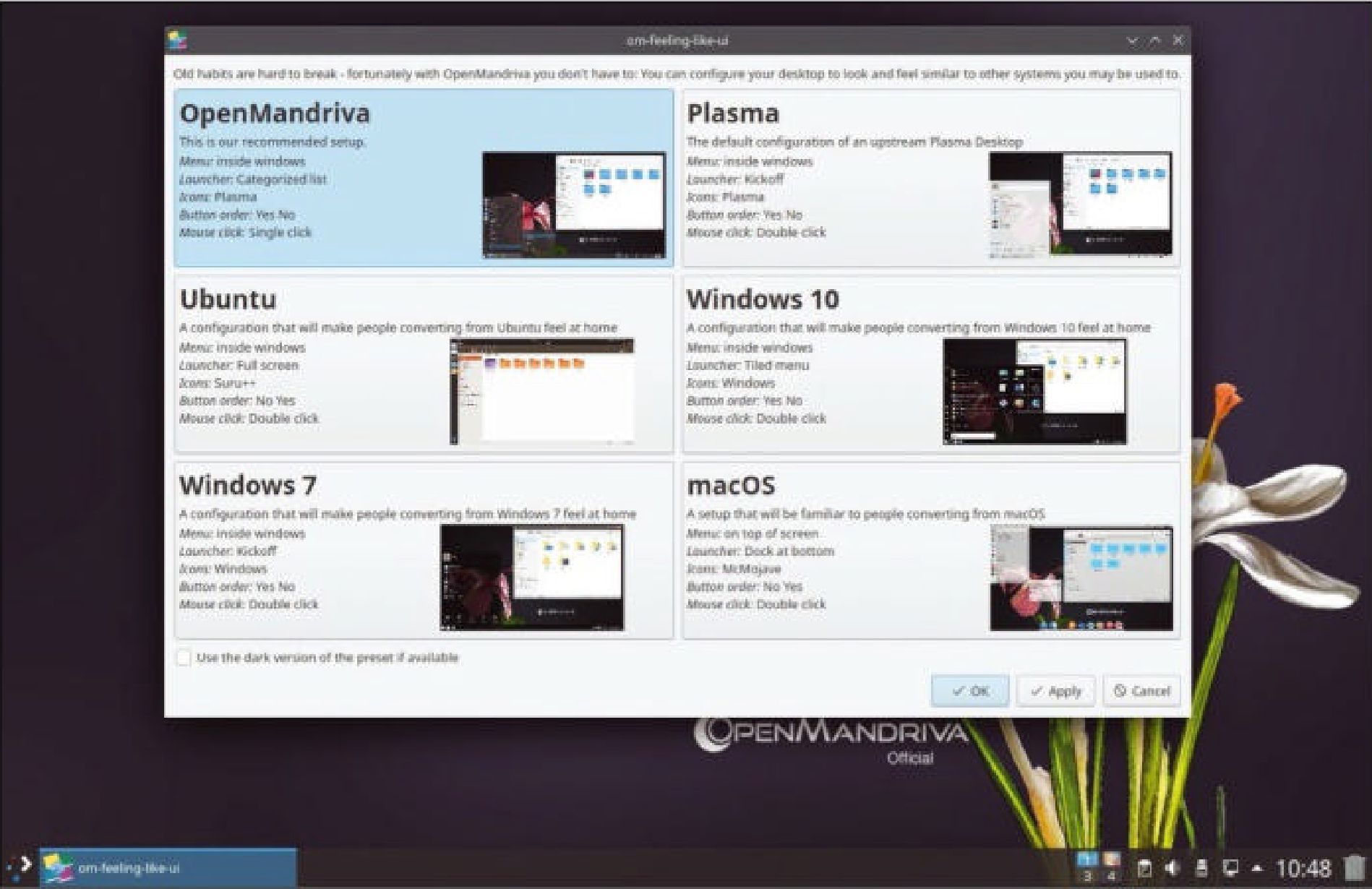

Figure 3: Like Zorin, OpenMandriva LX can mimic other operating systems as an aid to new users.

While OpenMandriva does not hesitate to borrow from other distributions when convenient, it definitely takes full advantage of its independence. For example, in 2016, OpenMandriva was the first distribution to be built with Clang as its main compilers, even before Android. Similarly, “using a different implementation of the tar command, we are exploring a more cross-compiler friendly filesystem layout making sys-roots more useful than ever, and we have started experimenting with builds using alternative libc implementations.

The distribution has also started to use an automated update tool for packages, which helps to ensure that even neglected packages are updated. On the desktop, the custom-built tools include Desktop Presets, a tool that can make OpenMandriva look more like Windows, macOS, or another Linux distribution” (Figure 3).

So, in answer to my original question, what happened to Mandrake? The answer is nothing. In OpenMandriva, Mandrake’s spirit lives on, the biggest change being the name. In 2023, the Mandrake branch of Linux is still going its own way and adding innovations to open source.

With thanks to rugyada, raphael, bero, and ben79.

Info

[1] OpenMandriva: https://www.openmandriva.org/

[2] Transfer of intellectual property: h ttps://wiki. openmandriva. org/en/ policies/oma-tm-licence-en

Author

Bruce Byfield is a computer journalist and a freelance writer and editor specializing in free and open source software. In addition to his writing projects, he also teaches live and e-learning courses. In his spare time, Bruce writes about Northwest Coast art (http://brucebyfield.wordpress.com). He is also co-founder of Prentice Pieces, a blog about writing and fantasy at https://prenticepieces.com/.